«No man is an island – he is a holon.»

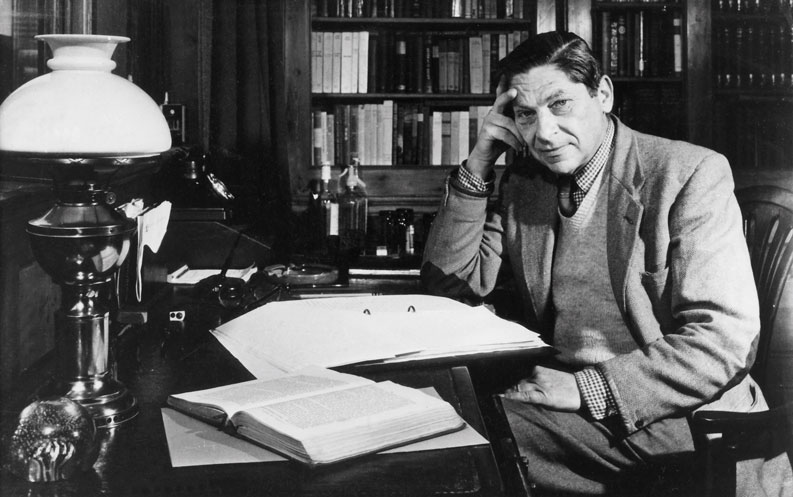

Arthur Koestler

Throughout the history of humanity, individuals have faced highly adverse circumstances that have contributed to their adaptability. Ironically, these circumstances have also diminished the likelihood of survival. Since mastering atomic energy as a weapon of mass destruction, humanity has turned the clock of its existence against itself. Unless a global balance is found between reason and emotion, ballistic missiles will continue to be designed to reach any continent, any planet, or any other place in the universe where this race may go. Simply leaving Earth for Mars or another location does not ensure survival if accompanied by an regressive and ambitious mindset. In such a scenario, only the magnates who can afford their salvation tickets will survive, diminishing the importance of rescuing the Earth’s habitat. This makes it more perilous for the middle and lower classes, unable to afford the ticket.

Numerous thinkers have endeavored to elucidate the machinery we call the human mind, offering methods and psychological currents for various cases. However, it is Arthur Koestler, a Hungarian-born novelist, essayist, historian, journalist, political activist, and social philosopher of Jewish origin, who attempted a more general and collective psychological analysis. He sought a cure for the collapse of civilization, even if he considered it a lost or nearly impossible cause.

The evolution of our species is crucial to understanding the inherent flaws leading to behavioral problems. However, this article focuses on the two tendencies identified by Koestler, which integrate a person as a «holon, an entity with a Janus-faced character, looking inward, seeing itself as a self-contained whole, and looking outward as a dependent part» (A. Koestler).

The self-assertive tendency, one face of Janus, is the inclination of humans to self-reinforce in various ways—through information, knowledge, self-love, self-cultivation, etc.—ensuring them as complete, independent beings capable of autonomous action.

On the other hand, the self-transcendent tendency, the other face of Janus, is the antagonist, expressing dependence on a broader context to which one belongs. It integrates an individual into a group, allowing the sharing of information acquired through self-assertive behavior and skills that lead to transcendent development.

The polarity of these tendencies is the focus of this article. An imbalanced inclination toward the self-transcendent tendency leads to obsessions with groups, fostering fanaticism in religious, political, economic, racial, and ideological domains. Understanding the defects of our species’ design is essential, but this article concentrates on the dual tendencies that Koestler identified.

Reason helps avoid falling into any form of fanaticism. Is war reasonable? Yes? No? Why? What are the motives for war—religion, ego, politics, power, racism, classism, desire for control? All share an unrestrained inclination toward self-transcendence, a desire for dominance and influence. This is where the influence of the self-assertive tendency becomes crucial.

In the privacy of my room, I can connect one word to another to articulate an idea due to the spelling rules learned in school. This common human learning experience reflects an innate tendency—perhaps genetic or physical—to self-reinforce, learn, and self-complete. This tendency is crucial in defining ourselves and in relating to others. It is the self-assertive tendency that integrates us into a group by making us «part» of it.

The imbalanced inclination toward this tendency results in complexes, such as Narcissus, and antisocial or extremist behaviors like suicide, which are not explored in this article.

Humans suffer from dementia, but the impact depends on one’s awareness, how it affects them, and the will to address it. The self-assertive and self-transcendent tendencies oscillate in waves, tied to our emotions. One dominates at a given moment, and the other prevails at another. Full awareness of this allows us to maintain a balance between these two faces of Janus, looking forward and inward without falling from virtue and reason, staying within the logical and just. Self-analysis allows us to transcend. Let us be free but mindful of our tendencies. This is a humble wish.

«Our gaze is that of the god who observes us.»

José Roberto Rivera Díaz

Deja una respuesta